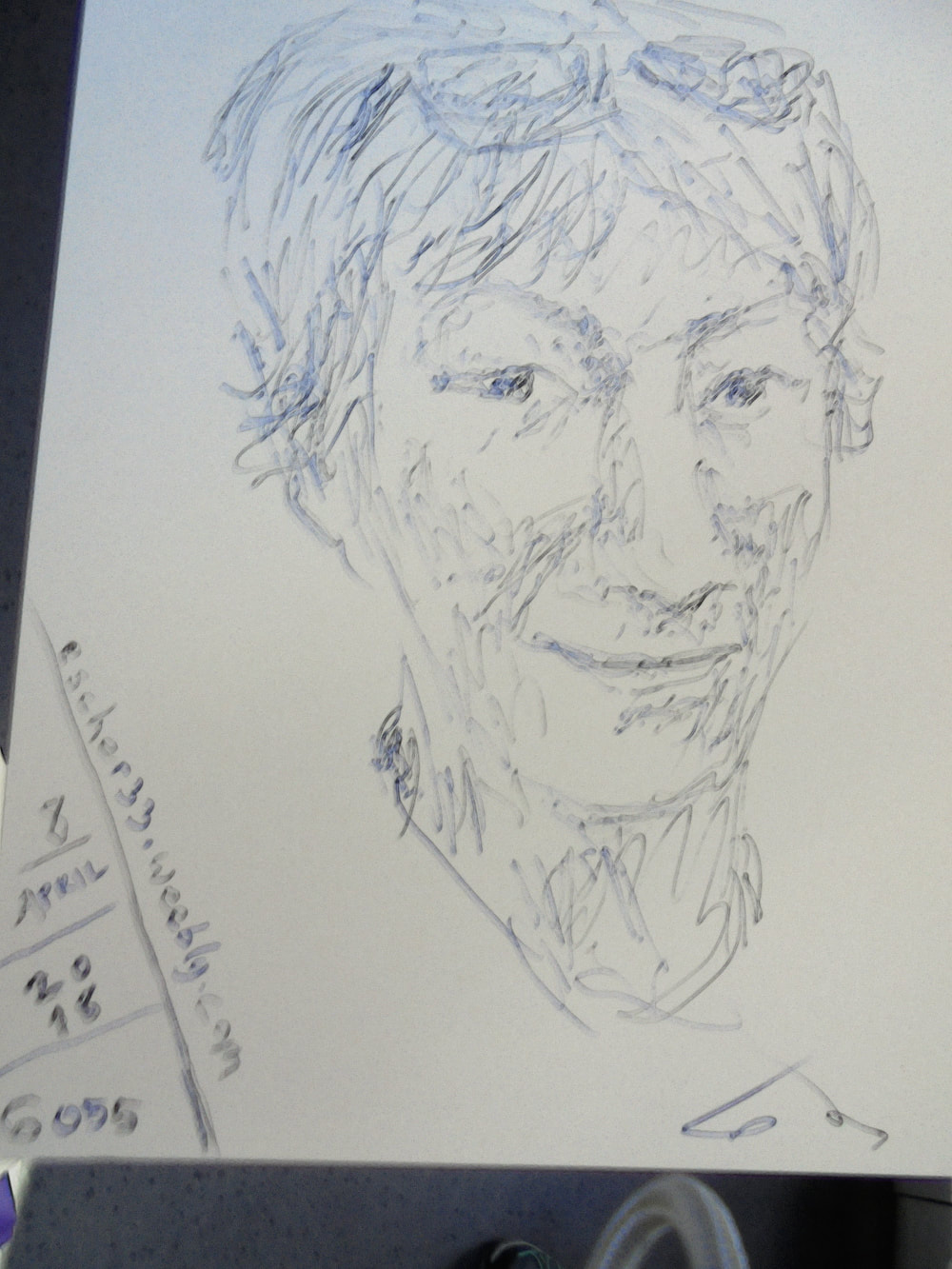

I get onto a Saturday afternoon train to the big city. Experience has taught me that while the elderly don’t pose a threat to me, here in Germany they often feel threatened by me—so I look for a place to sit near immigrants; near youngsters; near people under forty. Finding a seat on a train is like opening a pack of Pokémon cards: you never know what’ll you’ll get to work with. But you work with it. The new parents with mixed kids I had noticed go to sit in some far corner of the train. Before me instead are a group of elderly women. But they’re happy—even full of energy. I get to drawing the happiest one. Whispers begin, and soon smiles too. They are all abuzz with the drawing. They start a conversation with me. By the time I begin on the second elderly lady, even others on the train join in on the conversation. There is such a glow on that short ride. You can never know, until you try.

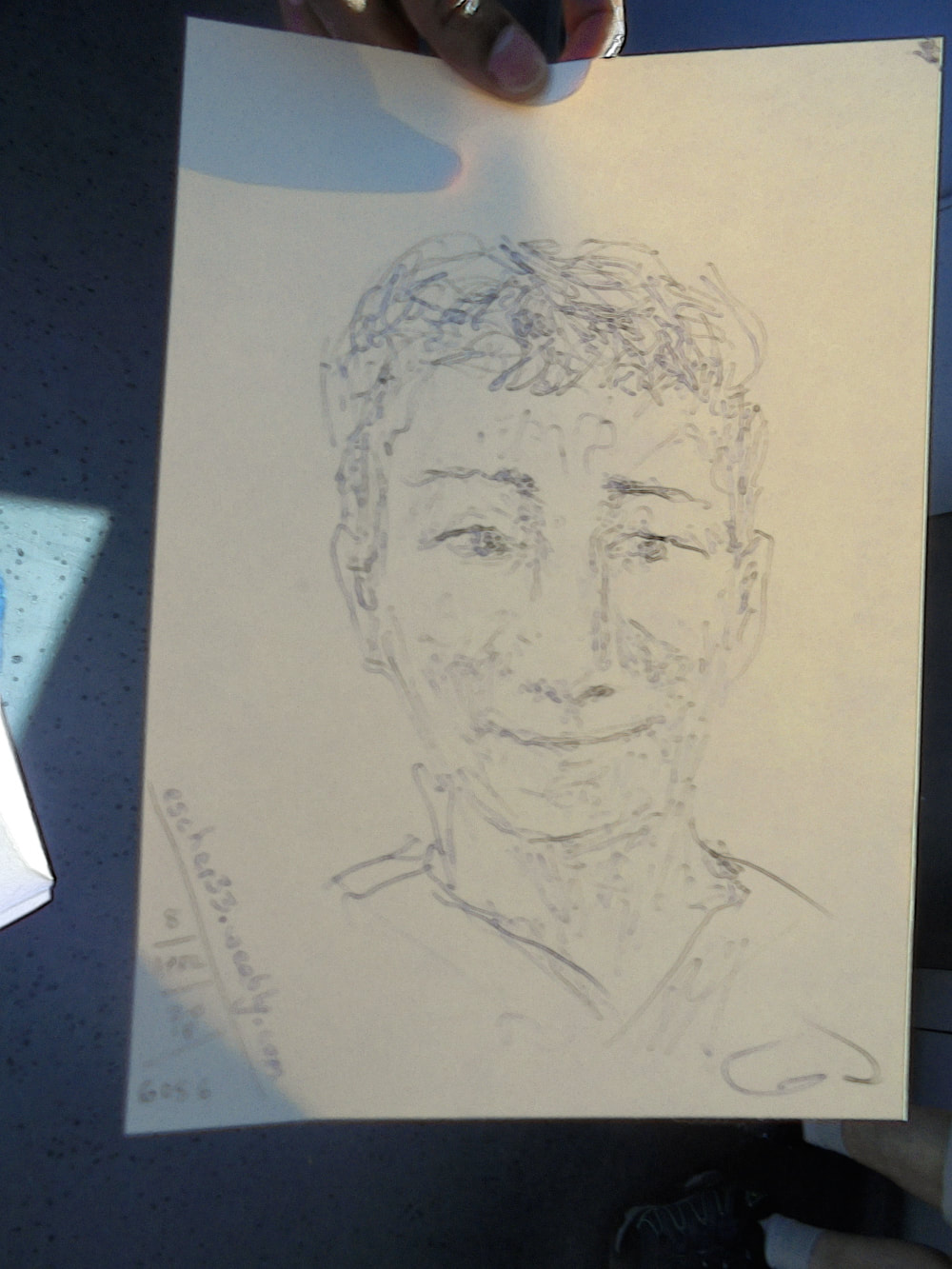

That was a short train ride, but this was a long journey. One train was finished, a much longer one was to begin. I wait by the platform until my connection arrives. I climb on, and walk from one train car to the next, trying to find a ‘nice deck.’ I settle for a seat next to some Taiwanese college students. Nǐ shì zhōngguó rén ma? (Are you a Chinese person?) I ask. A nice conversation ensues. After plenty of practice in Chinese, I begin to draw the one, then the other. Of course, the other eyes in the train are attracted even more by two-handed drawing than by a brown guy with an afro speaking Chinese. One older German woman with a head of white hair is especially leaning over to watch. So after drawing a third person on the train, I begin to draw the older woman who was so curious.

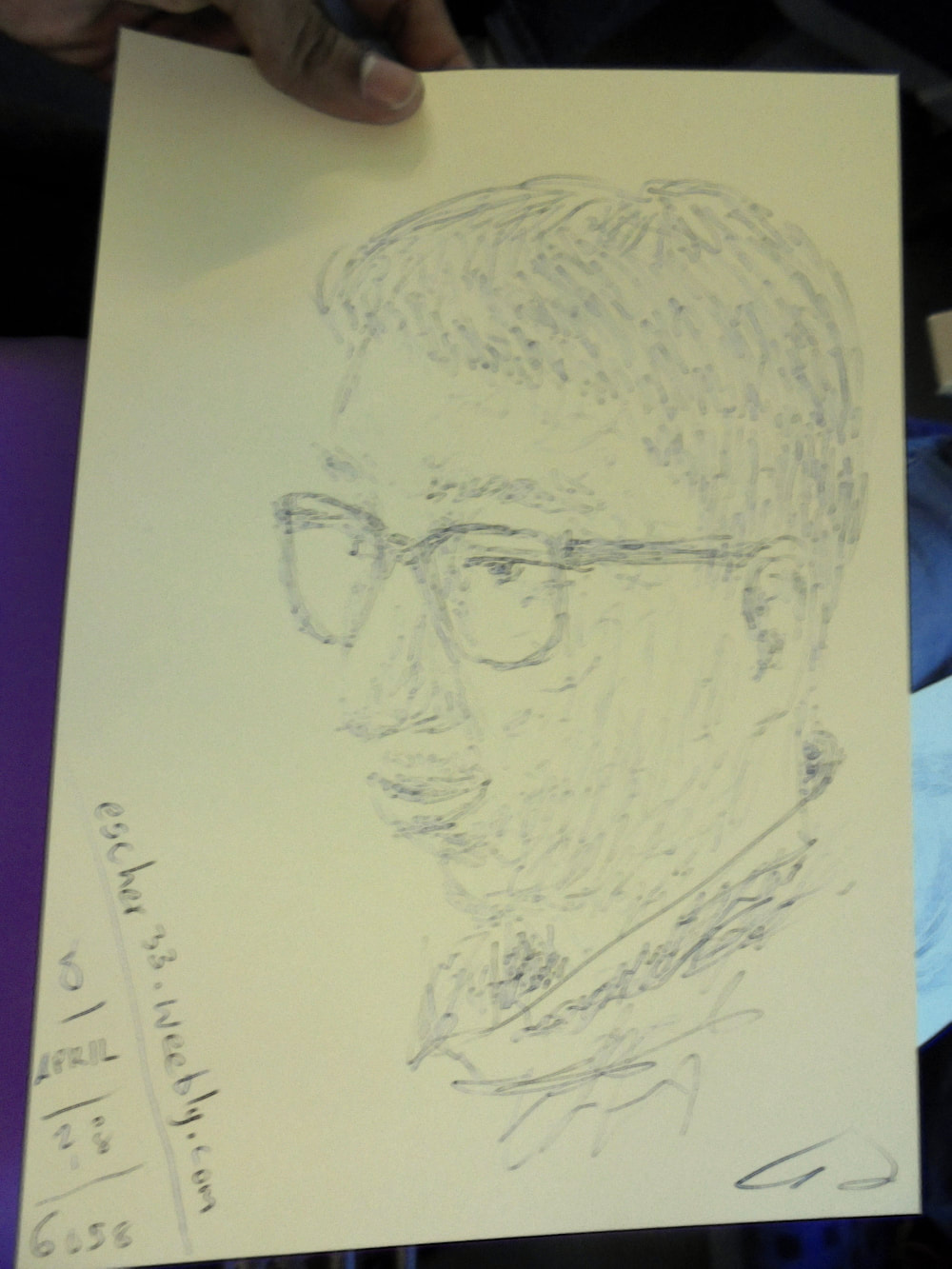

“No! I don’t want a portrait,” she says in English, sharply. I’m not expecting this. “You’re not allowed to draw someone’s picture without asking them first. It’s just like taking a photograph.” She sternly explains, still in English. Woah. I’ve only had this kind of negative response three times before—even after six-thousand portraits in ten countries! It never feels good. You don’t want a portrait, and that’s fine, I explain to the white-haired woman in German. But I have a reason for not asking. I can say, ‘this is free,’ ‘it costs nothing,’ ‘it’s just my hobby, I’ve drawn six-thousand portraits before you,’ and people will still ask: “but how much does it cost?” People look at my curly afro and my dark skin and think I am a refugee, who must be struggling for one or two Euros more. I’m American, working here as a software developer, but no words I can say, no way I can ask can break through this pre-conception. She is now surprised. She recognizes that what may be easy for her to do as a German woman is a lot more complicated for someone like me. I’m watching her reaction. I’m not talking for my benefit, I really want her to know this. I really want her to understand this. I really want to challenge her perception of me she began the conversation with. So I seek measured words.

“OK, you’re American, I know Americans. My daughter lives in Colorado. But you’re not really from America, you immigrated there from somewhere, right?” She asks, switching the conversation again to English. Wooph. It’s one of the hardest things you can do: change a person’s mind, when they don’t want it changed. I was born in America. I respond slowly in German, My dad came from this place, my mom from that place, and I studied in California. “You studied art there?” I studied mathematics there. I don’t fit in any of her boxes. As the conversation continues, she is only more and more surprised.

She doesn’t like me, but she can’t stop asking questions. We talk, it turns out, until we reach the end of the line—more than half an hour. I still have more of a journey ahead of me. Before I take my leave, I say a few words: I apologize if I offended you in not asking. But I hope you understand now why I didn’t ask. “Oh, it’s OK,” she says, making a face. “I forgive you.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed